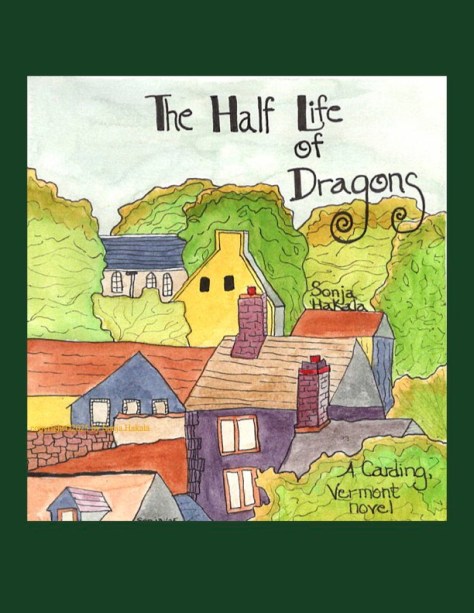

~ Here is the first chapter of my latest novel, The Half Life of Dragons. Enjoy!

~ Sonja Hakala

People who pass through Carding, Vermont on their way from here to there probably write the town off as “quaint” or “sleepy,” good for a maple creemee or a scenic photograph or two but not much else. And the people who consider themselves fortunate enough to have a Carding address for snail-mail gladly agree with that assessment.

Keeps down the riffraff, they like to say.

But of course the quiet part is not true. Lots goes on in Carding—sorrows, joys, difficulties, and triumphs. It’s just that Carding-ites prefer not to be too fussed about folks-from-away or their concerns. That’s why they live where they do.

In spite of keeping themselves to themselves, they do discuss and debate great national issues with the same fervor they devoted to a ballot measure at a recent town meeting. It was a question of money, not a whole lot, mind. But it was enough—$9,087—to whip up the spirit of the parsimonious contingent who felt they would not live up to their reputations if they did not object to something beore the meeting was adjourned.

David Tarkiainen, recently retired high school history teacher, had spearheaded the ballot measure. As chair of the cemetery committee—a nice, quiet way to contribute to town affairs—he thought he was doing due diligence by alerting the populace to the rather haphazard condition of the graveyard records. In fact, he’d uncovered a crop of headstones near the ruins of a barn that had never been recorded at all.

The money, he explained patiently, was to pay someone to digitize all the existing records. David, he again explained patiently, and his committee of three planned to contribute their time to walk each cemetery in order to make sure that the records were accurate and complete.

“Sounds like a good deal to me,” Ruth Goodwin said when she got to contribute to the town meeting conversation.

“I agree with Ruth,” Wil Bennet said. He had just turned eighteen, and was eager to take part in a ritual he’d watched since he could crawl.

“Oh you’re just saying that because Ruth is your grandmother’s friend,” Max Goodwin growled from his front road seat.

“And you’re just making waves, Max, because Ruth is your ex-wife, and you like to ruffle her feathers,” Andy Cooper said. Laughter rippled through the high school gym.

No one knew exactly how he did it, but Max had a way of making the remaining hair on his head bristle whenever he got steamed up for a tirade. The hair warning system had just been engaged when Agnes Findley leaped to her feet. “I call the question,” she shouted.

Several people whose backsides were growing numb from spending too much time on the gym’s benches, stood to applaud as moderator Charlie Cooper announced it was time to vote. The measure passed, of course, because after you’ve approved nearly a million dollars for a new fire truck, $9,087 seems like pocket change. Max Goodwin began to bubble and boil but his protests were drowned out by the lively chatter that always accompanies the end of a town meeting. Ruth, who was happy to be called his ex-wife, shook her head as his latest Princess—Max called all this wives Princess because it was easier than remembering new names—tried to calm him down.

“I’m glad that’s not me any more,” she said to Edie as they walked out together.

“Really? I’m surprised to hear you say that because I don’t remember you ever trying to calm him down,” Edie said.

“Exactly,” Ruth replied, and the two of them laughed.

Their exit was interrupted by David Tarkiainen. “Thanks for speaking up, Ruth,” he said. “I wasn’t looking forward to dealing with Max. He can be a bit touchy.”

“Oh, you know it would have passed, Dave. Max just wanted attention. No one was going to listen to him or vote with him,” Ruth said. “We go through this every year.”

“Well, you’ve got to remember I’m still a relative newcomer to Carding,” he said.

Edie puckered up her face. “How long have you lived here?”

“Only five years,” Dave said.

“But you were born in Vermont, right?”

“Yep, grew up in the big city of Burlington,” he said.

“Ah well, we’ll let you stay in spite of that,” Edie said with a grin. “So when are you planning to start your cemetery tour?”

“Well, I walked the perimeter of the big one behind the Episcopal Church yesterday to see if the ground had firmed up enough for a group, and I estimate we could use another week of drying,” Dave said. “So I’m thinking we could start next Saturday, if that works for folks. I’d like to get out before the grass really gets going.”

“Could you use another volunteer or two?”

Dave’s eyes began to shine. “Are you offering?”

“Absolutely,” the two women said.

“Okay then, I will put you on my list.”

__________________

In Vermont, the arrival of spring is uneven. Depending on how low in a valley or how high up on a mountain a parcel of land sits, its location in the early spring sun determines when its frost finally leaves the ground. So when David plotted out his cemetery walking tour, he started on the low ground at the center of Carding near the Corvus River then slowly spiraled out and up Mount Merino in one direction and Belmont Hill in the other.

There were five of them, the cemetery walkers, and they quickly became a convivial group. They checked checklists and paused to run their fingertips over the faint markings on the oldest headstones in an effort to make out their lettering. They were all surprised to learn how many cemeteries dotted the Carding landscape, from the biggest at the Episcopal church to a small family plot owned by the Tennyson family way up on Belmont Hill.

By general consensus, the five walkers saved the graveyard at the Community Church until the early daffodils began to bloom in April. In the old days, the small, white church had been a center of village life. But now, it didn’t get many visitors because the two wood stoves that used to keep the congregation somewhat warm had been removed for fear of fire. So from the end of foliage season until the arrival of daffodils, the Community Church of Carding, Vermont kept a lonely vigil on the nob of Priory Hill. But as the bonds of winter loosened, the shoulders of the 1830-ish building relaxed in the sun and visitors began to trickle back.

There was a lot to see in this house of worship, if you were the type to appreciate skilled craftsmanship. The rafters and joists, visible from the floor, were hand hewn from oak felled on the property. The sun had toasted the church’s wood siding to a deep honey-brown. Inside, the plastered walls kissed the angle of the roof eight feet above the parishioners’ heads. If you knew what you were looking for, you could identify the work of each man who had used a trowel on them. Some parts of the walls were as smooth as a tight bed sheet while other places were rumpled, as if the sheet had been slept on. And there was one small section behind the altar where children had pressed their hands into the mix of lime, water, and sand while it was still wet.

Rows of tall windows welcomed the light on three sides of the building. Their glass had rippled with age so it was difficult if not impossible to discern who was standing outside. If you timed your visit carefully, especially around the spring and fall equinoxes, you could enjoy a display of tiny rainbows prismed onto the plaster through the wavy glass. More than one child in Carding grew up believing that fairies danced in the old church.

Over the decades, the building had become something of an icon for artists, and painting it is something of a rite of passage in this part of New England. Many of those paintings and drawing hang among the church’s windows, lovingly put up and taken down with the passing of the seasons.

You could chart the church’s history in the paintings by remarking the size of the maple planted just outside its front door when the building was consecrated. An unknown itinerant artist was the first to paint it, back when the tree was a mere sapling. An early pastor was the second to sketch the church, using the pages of a notebook where he jotted ideas for his sermons. The tree grew in every successive painting. There it was on a spring day with the blooms of an apple orchard stretching off in the distance behind the church. And there it was again in winter, cradling snow in its arms while candles glowed in the sanctuary’s frosted windows.

With the last of the winter snows finally gone, it became a perfect spring day for cemetery walking, still cool enough for a jacket but with no need for a scarf or mittens. The walkers gloried in the sea of daffodils that covered the lawn, bees busy among them, mining nectar.

“I never thought I’d say this, but I’m going to miss our walks,” Ruth said as the group set out, checklists in hand.

“Me too,” David said. “I’ve learned so much about Carding, and the families who came here. I’m wondering if we should make this an annual thing in order to check on the local conditions, and to keep the records up to date.”

“That’s not a bad idea,” Edie said as she strolled off. “I’m going to start in that far corner and work my way around.”

There was no sound but bird song for a while. David was immediately drawn to the church building, and circled its perimeter with one hand caressing the exterior wall as he admired the workmanship of the community that had raised it. He was drinking in the peace as he rounded the last corner when something crunched under his foot.

“Huh, what the…?”

Glass beads of all colors, hundreds of them, radiated out in a half circle from a grave marker fashioned from a paving stone resting on its edge. Someone had scrawled a name on it in black paint.

“Timmen Eldritch,” David whispered to himself. “Isn’t that…?” He shook his head in disbelief then raised his voice to call the others.

“What is it David?” Ruth said as she panted up to his side. Then she saw the stone. “Oh gawd, no.”

“Isn’t that the guy—the singer—who died while he was living here in Carding?” David asked.

“Not died,” Ruth said. “Disappeared. Under mysterious circumstances.”

Edie, John, and Wesley now joined them. “That’s the guy from that band, Calliope,” Wesley said, pointing. “Oh they were a bad news lot.”

“That thing’s a fake,” John said. “Eldritch was never found, never declared dead. There was no funeral for him. No burial either. Someone has a really sick sense of humor to put that up. Let’s get rid of it before the Calliope vermin start making pilgrimages up here.”

He reached down to pick up some of the glass beads but Edie stopped him. “You’re right about getting rid of this, John. But we need a record of it. Let’s all take pictures and then call the police. It may not be destructive but this is a sort of vandalism.”

“I just hope no one’s put it on social media or the vermin will overrun this place,” Ruth said.

“Too late.” Wesley tapped on his phone’s screen then turned it so that his friends could see an image of the false grave with the words “Eldritch Burial Found” emblazoned across the top.

Thanks for sharing some of the minutes of your life with me and Carding, Vermont. I hope you enjoy The Half Life of Dragons and can visit next week for the latest chapter.

When I reach the end of the tale, the entire book will be available here as an ebook.

~ Sonja Hakala